Back to Basics: The Vapor-Compression Refrigeration Cycle

Key Highlights

- Refrigeration involves moving heat from one place to another, primarily using the vapor-compression cycle in HVACR systems.

- Phase changes, such as boiling and condensation, enable refrigerants to absorb or reject large amounts of heat efficiently.

- Superheat and subcooling describe the states of refrigerant vapor and liquid relative to saturation, crucial for system performance.

While it’s pretty safe to say that most people will hear “refrigeration” and automatically think about keeping stuff cold, the word actually has a much different meaning to HVACR professionals. It’s not all about cold; refrigeration is the process of moving heat from one place to another. Most HVAC and refrigeration systems achieve this with the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, which manipulates heat by taking advantage of natural thermodynamics.

Thermodynamics, Heat, and Temperature

Thermodynamics is an expansive field of study, but it’s also just a fancy way to say “how heat moves and transforms.” Now, heat is not the same thing as temperature. Heat is the transfer of thermal energy between two things due to a temperature difference. We measure it in British thermal units (Btu), and it is released when stored energy (potential) becomes active (kinetic). When that happens, molecules have more energy and start moving faster. The molecules that vibrated slowly in a log at rest speed up rapidly when it burns. The average intensity of those molecules’ movement is the temperature, measured in degrees (usually in the Fahrenheit or Celsius scales).

An example I like to use to illustrate the difference between heat and temperature is comparing an 80° F swimming pool to a 120° F cup of water. While the cup of water has a higher temperature, molecules are moving faster, on average, than in the swimming pool; many more molecules are moving around in the swimming pool. Therefore, the overall heat content of the swimming pool is greater in that more Btu would move if there was a temperature difference, but the cup of water has the more intense molecular motion.

Heat moves quite predictably in nature, from hot to cold until both objects are the same temperature. The faster-moving molecules will move toward the slower-moving molecules until they’re both the same speed. If you brew a cup of hot coffee and leave it in a 75° F room for an hour or two, it’ll be lukewarm by the time you come back. That’s because heat leaves the coffee and goes to the air around it. The air immediately above the cup of coffee may be warmer as this heat transfer happens, but with time, the temperature will even out entirely. That’s the second law of thermodynamics at work.

We want to get heat out of our homes, vehicles, and refrigerators, but those spaces are usually colder than their surroundings. We can’t exactly depend on the second law of thermodynamics to help us, since heat doesn’t naturally move from cold to hot… or can we?

Moving Heat With Something Other Than Air

Moving the colder air in a home or refrigerated case to a warmer place is out of the question if we’re using that same air to transport that heat. But we could use another medium to transfer the heat and cool the air.

John Gorrie (1803–1855) tried it first. Gorrie was a doctor in Apalachicola and used ice to cool the rooms of his patients with malaria. At the time, the ice trade was in full swing, but he wondered if he could create ice on his own. He invented a machine that compressed and expanded air in a cycle. These changes in pressure (compression = higher, expansion = lower) enabled the transport of heat away from water, which made it freeze into bricks of ice. Unfortunately, Gorrie faced financial ruin, and he died without his machine ever becoming mainstream.

Nowadays, we use different fluids to absorb the heat from buildings and refrigerated boxes and move it somewhere else. These fluids, refrigerants, are compressed and expanded as in Gorrie’s invention, but they also switch between the vapor and liquid states as they absorb heat from one place and reject it somewhere else.

Phase Changes

In school, you probably learned the three phases of matter: solid, liquid, and gas (we can also get fancy and say plasma, but that’s not relevant here). “Fluids” refer to liquids and gases. In the case of refrigerant, it switches between liquid and vapor (a type of gas). But why would this be advantageous over Gorrie’s design?

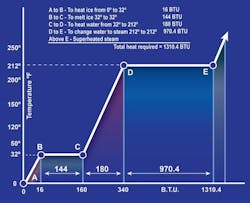

It’s the same reason why boiling water at sea level doesn’t go above 212° F the entire time it’s boiling. All the heat that goes into the water while it’s boiling goes toward turning it into a vapor, not toward temperature increase. As said earlier, we measure heat in units called Btu; it only takes 1 Btu to raise the temperature of a pound of water by one degree, but it takes 970 Btu to boil that pound of water.

We don’t see or feel any changes, but that heat still exists, which is why we call the heat that contributes to a phase change latent heat. On the other hand, the heat we can feel and that contributes to a temperature change is called sensible heat.

If we apply that to refrigerant, that latent heat allows systems to absorb or reject a lot more heat during a phase change than if the system just absorbed sensible heat in the vapor or liquid form.

Saturation, Superheat, and Subcooling

When a fluid is boiling or condensing, we call that saturation. Substances are vapors when their temperatures are above saturation, and they’re liquids when below. When vapors have a higher temperature than their saturation point, the difference between their temperature and saturation is called superheat. Let’s say we have water vapor at 219° F. Considering that saturation is 212° F, we have 7° F of superheat. When liquid is below saturation, the difference between its temperature and saturation is called subcooling. If we have 190° F water, its subcooling is 22° F.

Eugene Silberstein, one of the co-authors of "Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Technology," has a helpful way to think of superheat, subcooling, and saturation with an ocean horizon metaphor. The line where the water meets the air is the saturation point because liquid and vapor are in the same space. Above that line, you have air (vapor), where superheroes can fly (superheat). Below that line, you have water (liquid), where submarines explore (subcooling).

The vapor-compression refrigeration cycle, or the refrigerant circuit, has refrigerant in its saturated, superheated vapor, and subcooled liquid states. Again, in order to achieve this range of states, we have parts that are dedicated to absorbing and rejecting heat, as well as raising or dropping the pressure.

Editor's Note: Next month, Bryan Orr's Back to Basics series will continue with the four elements of the vapor-compression refrigeration cycle.

About the Author

Bryan Orr

Bryan Orr is the president and co-founder of Kalos Services, a multi-trade contracting company in Central Florida. He started in the field and built Kalos from a two-person HVAC shop into a large HVAC, refrigeration, electrical, plumbing, and construction team. He also founded HVACRSchool.com, a training platform and podcast used by techs across the industry. Orr focuses on solid processes, real technical skill, and developing the next generation of tradespeople while keeping the straightforward, field-driven values he learned on service calls.