The Top 3 Reasons You Shouldn’t Oversize Inverter-Based Equipment

Key Highlights

- Oversized inverters can increase static pressure, reduce airflow, and cause system failures such as compressor and heat exchanger damage.

- Proper dehumidification depends on the system's sensible heat factor (SHF); oversizing may impair dehumidification performance, especially if low-speed data is unavailable.

- Load matching is crucial; oversized inverters may not ramp up fully, leading to inefficient operation and increased wear on compressor oil return modes.

A few years ago, there was a debate on Facebook about sizing inverter-based equipment. I commented, “An oversized inverter is the most expensive single-stage unit you can install.” At the time, I thought it was a clever way to visualize how an improperly sized inverter might operate. That comment drew some attention, and I have heard it quoted several times in other inverter-sizing discussions.

It feels like Deja Vu every time this topic comes up. It’s always the same; the other person mutters, “You can’t oversize an inverter because it will just ramp down.” I understand why people might believe this, but there are several factors you should consider before installing that next 5-ton inverter-based unit.

1. Airflow Requirements

It is the job of HVAC professionals to add or remove heat (Btu) from a space. Air is the vehicle that transports those Btu, and it must be correct from the start. Otherwise, the equipment won't operate at its rated capacity.

In 2018, the Department of Energy (DOE) reviewed a study titled “Residential HVAC Installation Practices: A Review of Research Findings.” The study found that fewer than one-in-three residential systems move enough airflow. In other words, you could say that most systems have inadequate fan airflow.

Static pressure and fan airflow go hand in hand. You need to consider both to understand the full picture. National Comfort Institute (NCI) analyzed static pressure tests from contractors across North America and found that the average HVAC system operates at a Total External Static Pressure (TESP) of 0.82 inches of water column (in. w.c.). Most residential fans are rated at 0.50 in. w.c., indicating that most equipment is running at excessive TESP.

Increasing equipment size increases the required fan airflow. If most systems are operating at high static pressure and low fan airflow, what do you think happens when you install a larger unit? If you said the problem gets worse, you would be correct. Static pressure moves at the square of airflow. As you increase fan airflow, the static pressure can go through the roof.

Problems caused by high static pressure and low fan airflow include:

- Reduced efficiency — high blower watt draw;

- Blower motor faults/failure;

- Heat exchanger failure;

- Compressor failure; and

- Frozen evaporator coils.

A common method to counteract this is to lower the fan speed setting. The industry standard is 400 cfm (cubic feet per minute) per ton, and the solution is to commission the air-moving equipment at 350 cfm per ton.

Keep in mind, by doing so, the equipment will have a lower sensible heat factor (SHF). A lower SHF means less sensible capacity and lower efficiency. If you commission a system to move less Btu by lowering the fan speed, what is the point of installing the larger system to begin with?

2. Ensuring Proper Dehumidification

SHF is represented as a decimal and calculated as follows:

When the SHF is close to 1.0, the equipment is extremely efficient and does very little dehumidification. The lower the SHF, the greater the latent capacity/dehumidification the equipment can achieve. But, it is also less efficient than a system with a higher SHF. The reason: it takes a lot of energy to convert one pound of water vapor into one pound of liquid water, 970 Btu to be exact!

Some people think inverters do a great job at dehumidification at low compressor speeds, while others think they do a horrible job. In reality, they are both correct! It depends on what system you are referring to. However, there are times when the capacity is a mystery because some manufacturers don’t publish performance data below 100% capacity.

If you oversize an inverter without any published performance data at minimum compressor speeds, will it dehumidify properly? Maybe. But then again, maybe not.

I looked at several different model inverters and found the following:

|

Brand A (SHF) |

Brand B (SHF) |

Brand C (SHF) |

|||

|

Low Speed |

0.98 |

Low Speed |

0.74 |

Low Speed |

Unknown |

|

High Speed |

0.82 |

High Speed |

0.78 |

High Speed |

0.79 |

That leads me to my next question: What if the equipment has a dehumidification mode?

Dehumidification mode works on most inverters by speeding up the compressor while slowing down the blower motor. This mode does two things really well:

1. It creates a really cold evaporator coil (dehumidifies); and

2. It reduces the SHF.

A byproduct of a low SHF is a less efficient system. So, if a system operates mostly in dehumidification mode, it is operating at a lower SEER/SEER2 than the manufacturer rated it. What is the point of installing a 20 SEER unit if it only operates at 16 SEER? How do you think your customer would feel if they knew their new 20 SEER system operates at 16 SEER?

3. Load Matching Capabilities

An ideal inverter can match the home's load across a wide range of outdoor temperatures. A well-designed system will take advantage of the entire range of compressor speeds.

It is important for an inverter to run at full compressor speed to maintain oil return to the compressor. Oversized inverters won't naturally ramp up to their full capacity, which forces the compressor to use oil return mode more frequently. Oil return mode occurs when the control notices that the compressor hasn’t ramped up for a long period and forces it to speed up to maintain lubrication.

Think about driving your car in heavy traffic at very low speeds and having to rev the engine every so often. Does this sound like an efficient way of operating?

The Truth is in the Bin Data

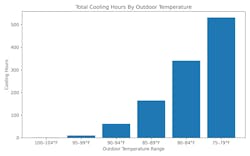

Think of bin data as buckets labeled by 5° F outdoor temperature ranges. We fill those buckets with the number of hours a specific location has experienced an outdoor temperature within that range. By looking at the bin data, it is easy to analyze how a system will operate when compared to the load of the building.

When designing a system, the best practice is to use the outdoor heating and cooling design temperatures. The average outdoor temperature is below the cooling design temperature 99% of the year, meaning it is warmer than the design temperature only 1% of the time, or roughly 88 hours.

The table above shows the 30-year bin data for the Chicago O’Hare weather station. The data shows that at times the outdoor temperature surpasses the 89-degree design temperature, but closely aligns with the 88 hours or 1% worst-case scenario.

Seeing this is what worries most contractors, leading them to oversize equipment. Chicago has experienced only one hour in the 100-104° F degree range in 30 years. One hour is not enough time to worry about systems not keeping up.

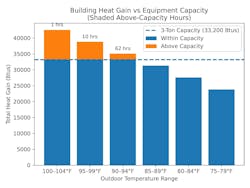

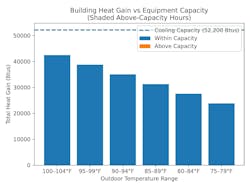

The following two charts are simplified data sets showing the building load, equipment capacity, and the hours spent in each bin.

Notice that a 5-ton unit will never ramp up to its full capacity, and, most of the time, will operate at a moderate compressor speed.

My statement, “An oversized inverter is the most expensive single-stage system you can install,” might not be entirely true. However, the equipment is definitely not being used as intended, and ultimately compromises comfort, efficiency, and longevity.

About the Author

Adam Mufich

content developer and instructor

Adam Mufich serves the HVAC industry as content developer and instructor for National Comfort Institute, Inc. (NCI). NCI specializes in training that focuses on improving, measuring, and verifying HVAC and Building Performance. Find them at www.nationalcomfortinstitute.com.